Storyteller

Traditional version control systems like CVS, Subversion, Git, and Mercurial store snapshots at commit points. Storyteller is different. Storyteller records almost all developer actions as they're made, stores them in a database, and has the ability to replay them at any time. There are powerful filters to limit the amount of information that gets played back.

More importantly, Storyteller lets developers create narratives about the playbacks. These narratives make up the stories about your system. Not every developer interaction warrants a story, only the interesting parts do. The stories are easy to create and are organized and searchable by the development team. Working on an existing piece of code that is new to you? Just highlight the code and see what stories were created about that code.

Developers need to learn how their systems evolve and how to become better programmers.

How does one debug code that hasn't been looked at in years? All of the important context information that was in the developers' heads surely fades over the time it takes a NASA mission to reach Mars. This historical information is important when adding new features or fixing a bug.

Of course, this problem is not unique to NASA missions. At most companies priorities shift, people shift, and it might be years before the development team is asked to revisit some code. In addition, new hires and transfers to active projects need to get that context information in their heads in order to be effective.

Version control systems (VCS) store snapshots of our documents over time. So, if one wants to recapture that context one can use VCS, right?

The Moving Picture Metaphor

The time in between VCS snapshots is too long to animate changes. The tools used to view the differences between snapshots make it hard to see how the code has evolved.

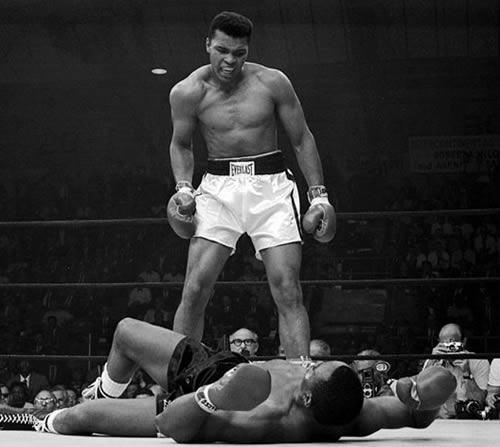

1965 Heavyweight Championship Fight. Sonny Liston (the gentleman on the floor) proceeded to get up! This was a 1st round TKO. The picture makes it seem like there was a long protracted battle. It was a rather uneventful fight, but an incredible picture.

This one still picture does not tell the whole story.

-

diff

With a diff tool one can see the differences between two sets of files, but this is hardly animated. What if one wanted to see the differences between three sets of code, or four? The exact details of how version one became version two do not make it into the VCS.

-

logs

On check in, developers write a commit message to the log. These logs could help animate the changes if developers wrote good messages. Unfortunately, they do not. It is too hard to write a good description of all the changes that take place from one commit to another.

The changes that developers make to code are typically not linear, instead they touch many different pieces of code in many different files. Remembering and describing why they made the changes in a commit message would be almost as hard as writing the code itself. A new form of program documentation is needed to easily describe why developers do the things they do.

-

code comments, documents, and other forms of documentation

Most developers have an aversion to writing documentation. When they are required to do it they often don't put in the effort needed to create an easily readable document.

It is a little bit easier to get developers to write code comments. Because developers love to write code and code comments are intimately linked to it, there is a great opportunity to store some kind of historical context here.

The problem is that it is hard to write a meaningful comment that is relevant in all contexts. For example, if a developer was changing the name of a variable from x to y, one could write a comment about why that change was needed. However, that comment is really only relevant to people who knew the old name and are interested in why the old name changed. Most people won't be interested in that comment so it is difficult to justify adding it to the code comments. This kind of information will stay in individual developer's heads for a little while but isn't likely to be stored anywhere else.

Moving pictures do a better job of telling a story than still pictures. Traditional VCS's don't store enough information and meta-information to animate the changes in a repository. If the code hasn't been looked at in a while, or there are new people joining the development team, a well documented and narrated animation can provide insight that would otherwise stay in only a few peoples heads and eventually escape into the ether.

How can we learn to become better craftsmen without being able to see how talented developers write code?

Right now, working on a computer is a solitary activity. Because of this, we can only reflect on our own experiences. Its difficult to get inspiration from others. We intend to change the way people learn at all stages of their careers by opening up for examination how people do their work.

Some people consider developing software a craft. Craftsmen learn by watching and working with more experienced craftsmen. However, we seem to go out of our way to hide how we do our work.

Because of a lack of animating tools it is hard to see how code has evolved. Labeled commits indicate the important milestones, but what about all the work that it took to get to that point? What can be learned from watching people go down a dead path? We believe there is a lot to learn from seeing this data in an animated playback.

The software development community is in need of tools that open up the development process to encourage learning by team members. It seems like we actively discourage openness and want people to believe we don't struggle to get to a final solution- we have to let go of this ego boosting fallacy. Even great developers struggle to come up with solutions to hard problems.

- It is critically important to see how people leverage good decisions and extend their position from them.

- It is critically important to see how people recover from bad decisions.

- It is critically important that we get feedback from 'masters' about why they are making decisions

When learning to play chess it is one thing to watch someone play chess as an outsider, it is considerably more valuable for that player to tell you why he is doing what he is doing, "In three moves this is going to pay off because I am going to be able to take your knight". This is exactly the kind of information that doesn't get recorded anywhere while writing code. This insight is extremely difficult to get other than learning the hard way. There should be an easier way to learn this.

It is also critically important that the craftsmen who make these decisions can comment about their work. They have to be able to tell stories. This is why people become apprentices- to watch, to hear stories, to discuss, and to get feedback from masters.

Questions? Comments? Suggestions? Contact Us for more information.